Fortunately, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in childhood is a rare event.

The OHCAO project has been collecting data from NHS ambulance Trusts regarding OHCA events in children under 18 years of age since 2014. Data collected from 2014 to 2022 indicated that the incidence of OHCA in children under 18 years in the UK was 5 per 100,000 children. The rates of OHCA in infants are generally much higher, which is often attributed to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

For the whole cohort, the median age of the children was 3.3 years old, and 58% were male. Whilst one-third of cases were witnessed, only 60% received bystander CPR. A medical cause was determined in two-thirds of cases, with 7% asphyxiation, 6% trauma, 2% drowning and 1% toxic ingestions (remaining aetiologies unknown). Only 6% of children had a shockable rhythm, and 60% presented in asystole.

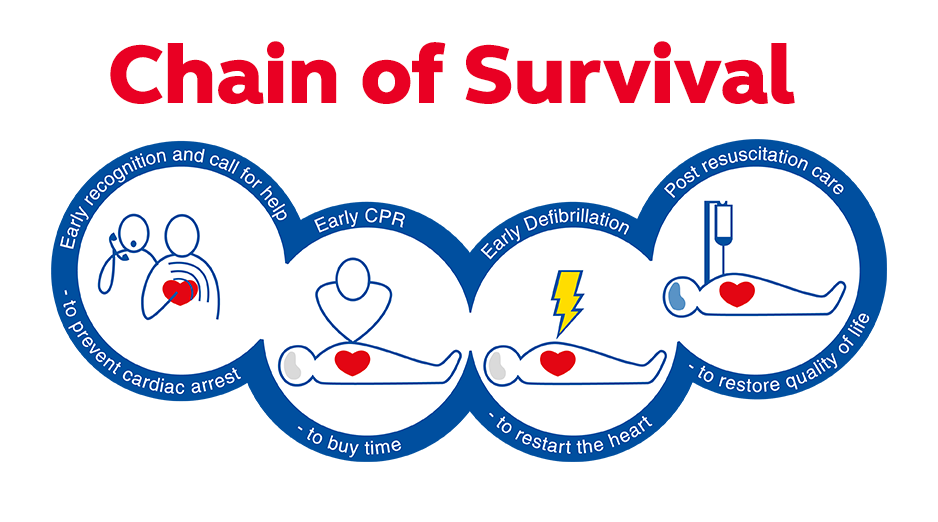

The overall outcome for return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) at hospital handover by emergency medical services teams was 18%, and survival to hospital discharge was 9.2%. However, this includes a small cohort of cardiac arrests from a primary cardiac cause (which includes cases referred to as “sudden cardiac arrest” or SCA). This is important as recognising symptoms and early use of a defibrillator will improve survival.

SCA is more common in boys than girls and is more likely to occur during or just after sporting activity. Warning symptoms for future SCA may include previous episodes of collapse or near-collapse, dizziness, palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath or unexplained episodes of brief seizure-like activity. Such symptoms may not always be present; however, they can be difficult to interpret in the setting of sporting activity, where those participating may often be pushing themselves to the point of exhaustion. A family history of cardiovascular disease and unexplained death at a young age may also be highly relevant.

Survival is more likely with witnessed events and a shockable rhythm on first ECG analysis - conditions often seen when an arrest occurs in a public location, like a school.